Traversal¶

A traversal uses the URL (Universal Resource Locator) to find a resource located in a resource tree, which is a set of nested dictionary-like objects. Traversal is done by using each segment of the path portion of the URL to navigate through the resource tree. You might think of this as looking up files and directories in a file system. Traversal walks down the path until it finds a published resource, analogous to a file system “directory” or “file”. The resource found as the result of a traversal becomes the context of the request. Then, the view lookup subsystem is used to find some view code willing to “publish” this resource by generating a response.

Using Traversal to map a URL to code is optional. It is often less easy to understand than URL dispatch, so if you’re a rank beginner, it probably makes sense to use URL dispatch to map URLs to code instead of traversal. In that case, you can skip this chapter.

Traversal Details¶

Traversal is dependent on information in a request

object. Every request object contains URL path information in

the PATH_INFO portion of the WSGI environment. The

PATH_INFO string is the portion of a request’s URL following the

hostname and port number, but before any query string elements or

fragment element. For example the PATH_INFO portion of the URL

http://example.com:8080/a/b/c?foo=1 is /a/b/c.

Traversal treats the PATH_INFO segment of a URL as a sequence of

path segments. For example, the PATH_INFO string /a/b/c is

converted to the sequence ['a', 'b', 'c'].

This path sequence is then used to descend through the resource

tree, looking up a resource for each path segment. Each lookup uses the

__getitem__ method of a resource in the tree.

For example, if the path info sequence is ['a', 'b', 'c']:

- Traversal starts by acquiring the root resource of the application by calling the root factory. The root factory can be configured to return whatever object is appropriate as the traversal root of your application.

- Next, the first element (

'a') is popped from the path segment sequence and is used as a key to lookup the corresponding resource in the root. This invokes the root resource’s__getitem__method using that value ('a') as an argument. - If the root resource “contains” a resource with key

'a', its__getitem__method will return it. The context temporarily becomes the “A” resource. - The next segment (

'b') is popped from the path sequence, and the “A” resource’s__getitem__is called with that value ('b') as an argument; we’ll presume it succeeds. - The “A” resource’s

__getitem__returns another resource, which we’ll call “B”. The context temporarily becomes the “B” resource.

Traversal continues until the path segment sequence is exhausted or a

path element cannot be resolved to a resource. In either case, the

context resource is the last object that the traversal

successfully resolved. If any resource found during traversal lacks a

__getitem__ method, or if its __getitem__ method raises a

KeyError, traversal ends immediately, and that resource becomes

the context.

The results of a traversal also include a view name. If

traversal ends before the path segment sequence is exhausted, the

view name is the next remaining path segment element. If the

traversal expends all of the path segments, then the view

name is the empty string ('').

The combination of the context resource and the view name found via traversal is used later in the same request by the view lookup subsystem to find a view callable. How Pyramid performs view lookup is explained within the View Configuration chapter.

The Resource Tree¶

The resource tree is a set of nested dictionary-like resource objects that begins with a root resource. In order to use traversal to resolve URLs to code, your application must supply a resource tree to Pyramid.

In order to supply a root resource for an application the Pyramid

Router is configured with a callback known as a root

factory. The root factory is supplied by the application, at startup

time, as the root_factory argument to the Configurator.

The root factory is a Python callable that accepts a request object, and returns the root object of the resource tree. A function, or class is typically used as an application’s root factory. Here’s an example of a simple root factory class:

1 2 3 | class Root(dict):

def __init__(self, request):

pass

|

Here’s an example of using this root factory within startup configuration, by

passing it to an instance of a Configurator named config:

1 | config = Configurator(root_factory=Root)

|

The root_factory argument to the

Configurator constructor registers this root

factory to be called to generate a root resource whenever a request

enters the application. The root factory registered this way is also

known as the global root factory. A root factory can alternately be

passed to the Configurator as a dotted Python name which can

refer to a root factory defined in a different module.

If no root factory is passed to the Pyramid

Configurator constructor, or if the root_factory value

specified is None, a default root factory is used. The default

root factory always returns a resource that has no child resources; it

is effectively empty.

Usually a root factory for a traversal-based application will be more

complicated than the above Root class; in particular it may be

associated with a database connection or another persistence mechanism.

Note

If the items contained within the resource tree are “persistent” (they have state that lasts longer than the execution of a single process), they become analogous to the concept of domain model objects used by many other frameworks.

The resource tree consists of container resources and leaf resources.

There is only one difference between a container resource and a leaf

resource: container resources possess a __getitem__ method (making it

“dictionary-like”) while leaf resources do not. The __getitem__ method

was chosen as the signifying difference between the two types of resources

because the presence of this method is how Python itself typically determines

whether an object is “containerish” or not (dictionary objects are

“containerish”).

Each container resource is presumed to be willing to return a child resource

or raise a KeyError based on a name passed to its __getitem__.

Leaf-level instances must not have a __getitem__. If instances that

you’d like to be leaves already happen to have a __getitem__ through some

historical inequity, you should subclass these resource types and cause their

__getitem__ methods to simply raise a KeyError. Or just disuse them

and think up another strategy.

Usually, the traversal root is a container resource, and as such it contains other resources. However, it doesn’t need to be a container. Your resource tree can be as shallow or as deep as you require.

In general, the resource tree is traversed beginning at its root resource

using a sequence of path elements described by the PATH_INFO of the

current request; if there are path segments, the root resource’s

__getitem__ is called with the next path segment, and it is expected to

return another resource. The resulting resource’s __getitem__ is called

with the very next path segment, and it is expected to return another

resource. This happens ad infinitum until all path segments are exhausted.

The Traversal Algorithm¶

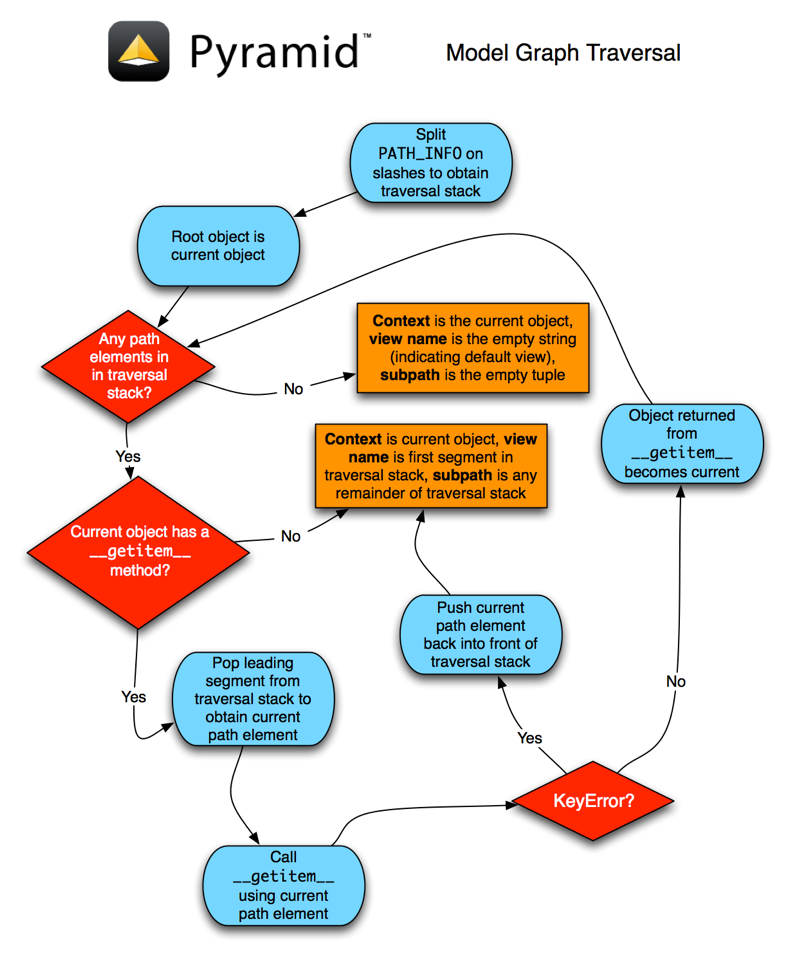

This section will attempt to explain the Pyramid traversal algorithm. We’ll provide a description of the algorithm, a diagram of how the algorithm works, and some example traversal scenarios that might help you understand how the algorithm operates against a specific resource tree.

We’ll also talk a bit about view lookup. The View Configuration chapter discusses view lookup in detail, and it is the canonical source for information about views. Technically, view lookup is a Pyramid subsystem that is separated from traversal entirely. However, we’ll describe the fundamental behavior of view lookup in the examples in the next few sections to give you an idea of how traversal and view lookup cooperate, because they are almost always used together.

A Description of The Traversal Algorithm¶

When a user requests a page from your traversal-powered application, the system uses this algorithm to find a context resource and a view name.

The request for the page is presented to the Pyramid router in terms of a standard WSGI request, which is represented by a WSGI environment and a WSGI

start_responsecallable.The router creates a request object based on the WSGI environment.

The root factory is called with the request. It returns a root resource.

The router uses the WSGI environment’s

PATH_INFOinformation to determine the path segments to traverse. The leading slash is stripped offPATH_INFO, and the remaining path segments are split on the slash character to form a traversal sequence.The traversal algorithm by default attempts to first URL-unquote and then Unicode-decode each path segment derived from

PATH_INFOfrom its natural byte string (strtype) representation. URL unquoting is performed using the Python standard libraryurllib.unquotefunction. Conversion from a URL-decoded string into Unicode is attempted using the UTF-8 encoding. If any URL-unquoted path segment inPATH_INFOis not decodeable using the UTF-8 decoding, aTypeErroris raised. A segment will be fully URL-unquoted and UTF8-decoded before it is passed in to the__getitem__of any resource during traversal.Thus, a request with a

PATH_INFOvariable of/a/b/cmaps to the traversal sequence[u'a', u'b', u'c'].Traversal begins at the root resource returned by the root factory. For the traversal sequence

[u'a', u'b', u'c'], the root resource’s__getitem__is called with the name'a'. Traversal continues through the sequence. In our example, if the root resource’s__getitem__called with the nameareturns a resource (aka resource “A”), that resource’s__getitem__is called with the name'b'. If resource “A” returns a resource “B” when asked for'b', resource B’s__getitem__is then asked for the name'c', and may return resource “C”.Traversal ends when a) the entire path is exhausted or b) when any resouce raises a

KeyErrorfrom its__getitem__or c) when any non-final path element traversal does not have a__getitem__method (resulting in aAttributeError) or d) when any path element is prefixed with the set of characters@@(indicating that the characters following the@@token should be treated as a view name).When traversal ends for any of the reasons in the previous step, the last resource found during traversal is deemed to be the context. If the path has been exhausted when traversal ends, the view name is deemed to be the empty string (

''). However, if the path was not exhausted before traversal terminated, the first remaining path segment is treated as the view name.Any subsequent path elements after the view name is found are deemed the subpath. The subpath is always a sequence of path segments that come from

PATH_INFOthat are “left over” after traversal has completed.

Once the context resource, the view name, and associated attributes such as the subpath are located, the job of traversal is finished. It passes back the information it obtained to its caller, the Pyramid Router, which subsequently invokes view lookup with the context and view name information.

The traversal algorithm exposes two special cases:

- You will often end up with a view name that is the empty string as the result of a particular traversal. This indicates that the view lookup machinery should look up the default view. The default view is a view that is registered with no name or a view which is registered with a name that equals the empty string.

- If any path segment element begins with the special characters

@@(think of them as goggles), the value of that segment minus the goggle characters is considered the view name immediately and traversal stops there. This allows you to address views that may have the same names as resource names in the tree unambiguously.

Finally, traversal is responsible for locating a virtual root. A virtual root is used during “virtual hosting”; see the Virtual Hosting chapter for information. We won’t speak more about it in this chapter.

Traversal Algorithm Examples¶

No one can be expected to understand the traversal algorithm by analogy and description alone, so let’s examine some traversal scenarios that use concrete URLs and resource tree compositions.

Let’s pretend the user asks for

http://example.com/foo/bar/baz/biz/buz.txt. The request’s PATH_INFO

in that case is /foo/bar/baz/biz/buz.txt. Let’s further pretend that

when this request comes in that we’re traversing the following resource tree:

/--

|

|-- foo

|

----bar

Here’s what happens:

traversaltraverses the root, and attempts to find “foo”, which it finds.traversaltraverses “foo”, and attempts to find “bar”, which it finds.traversaltraverses “bar”, and attempts to find “baz”, which it does not find (the “bar” resource raises aKeyErrorwhen asked for “baz”).

The fact that it does not find “baz” at this point does not signify an error condition. It signifies that:

- the context is the “bar” resource (the context is the last resource found during traversal).

- the view name is

baz - the subpath is

('biz', 'buz.txt')

At this point, traversal has ended, and view lookup begins.

Because it’s the “context” resource, the view lookup machinery examines “bar”

to find out what “type” it is. Let’s say it finds that the context is a

Bar type (because “bar” happens to be an instance of the class Bar).

Using the view name (baz) and the type, view lookup asks the

application registry this question:

- Please find me a view callable registered using a view

configuration with the name “baz” that can be used for the class

Bar.

Let’s say that view lookup finds no matching view type. In this circumstance, the Pyramid router returns the result of the not found view and the request ends.

However, for this tree:

/--

|

|-- foo

|

----bar

|

----baz

|

biz

The user asks for http://example.com/foo/bar/baz/biz/buz.txt

traversaltraverses “foo”, and attempts to find “bar”, which it finds.traversaltraverses “bar”, and attempts to find “baz”, which it finds.traversaltraverses “baz”, and attempts to find “biz”, which it finds.traversaltraverses “biz”, and attempts to find “buz.txt” which it does not find.

The fact that it does not find a resource related to “buz.txt” at this point does not signify an error condition. It signifies that:

- the context is the “biz” resource (the context is the last resource found during traversal).

- the view name is “buz.txt”

- the subpath is an empty sequence (

()).

At this point, traversal has ended, and view lookup begins.

Because it’s the “context” resource, the view lookup machinery examines the

“biz” resource to find out what “type” it is. Let’s say it finds that the

resource is a Biz type (because “biz” is an instance of the Python class

Biz). Using the view name (buz.txt) and the type, view

lookup asks the application registry this question:

- Please find me a view callable registered with a view

configuration with the name

buz.txtthat can be used for classBiz.

Let’s say that question is answered by the application registry; in such a

situation, the application registry returns a view callable. The

view callable is then called with the current WebOb request

as the sole argument: request; it is expected to return a response.

Using Resource Interfaces In View Configuration¶

Instead of registering your views with a context that names a Python

resource class, you can optionally register a view callable with a

context which is an interface. An interface can be attached

arbitrarily to any resource object. View lookup treats context interfaces

specially, and therefore the identity of a resource can be divorced from that

of the class which implements it. As a result, associating a view with an

interface can provide more flexibility for sharing a single view between two

or more different implementations of a resource type. For example, if two

resource objects of different Python class types share the same interface,

you can use the same view configuration to specify both of them as a

context.

In order to make use of interfaces in your application during view dispatch, you must create an interface and mark up your resource classes or instances with interface declarations that refer to this interface.

To attach an interface to a resource class, you define the interface and

use the zope.interface.implements() function to associate the interface

with the class.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 | from zope.interface import Interface

from zope.interface import implements

class IHello(Interface):

""" A marker interface """

class Hello(object):

implements(IHello)

|

To attach an interface to a resource instance, you define the interface and

use the zope.interface.alsoProvides() function to associate the

interface with the instance. This function mutates the instance in such a

way that the interface is attached to it.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 | from zope.interface import Interface

from zope.interface import alsoProvides

class IHello(Interface):

""" A marker interface """

class Hello(object):

pass

def make_hello():

hello = Hello()

alsoProvides(hello, IHello)

return hello

|

Regardless of how you associate an interface, with a resource instance, or a

resource class, the resulting code to associate that interface with a view

callable is the same. Assuming the above code that defines an IHello

interface lives in the root of your application, and its module is named

“resources.py”, the interface declaration below will associate the

mypackage.views.hello_world view with resources that implement, or

provide, this interface.

1 2 3 4 | # config is an instance of pyramid.config.Configurator

config.add_view('mypackage.views.hello_world', name='hello.html',

context='mypackage.resources.IHello')

|

Any time a resource that is determined to be the context provides

this interface, and a view named hello.html is looked up against it as

per the URL, the mypackage.views.hello_world view callable will be

invoked.

Note, in cases where a view is registered against a resource class, and a

view is also registered against an interface that the resource class

implements, an ambiguity arises. Views registered for the resource class take

precedence over any views registered for any interface the resource class

implements. Thus, if one view configuration names a context of both the

class type of a resource, and another view configuration names a context

of interface implemented by the resource’s class, and both view

configurations are otherwise identical, the view registered for the context’s

class will “win”.

For more information about defining resources with interfaces for use within view configuration, see Resources Which Implement Interfaces.

References¶

A tutorial showing how traversal can be used within a Pyramid application exists in ZODB + Traversal Wiki Tutorial.

See the View Configuration chapter for detailed information about view lookup.

The pyramid.traversal module contains API functions that deal with

traversal, such as traversal invocation from within application code.

The pyramid.request.Request.resource_url() method generates a URL when

given a resource retrieved from a resource tree.